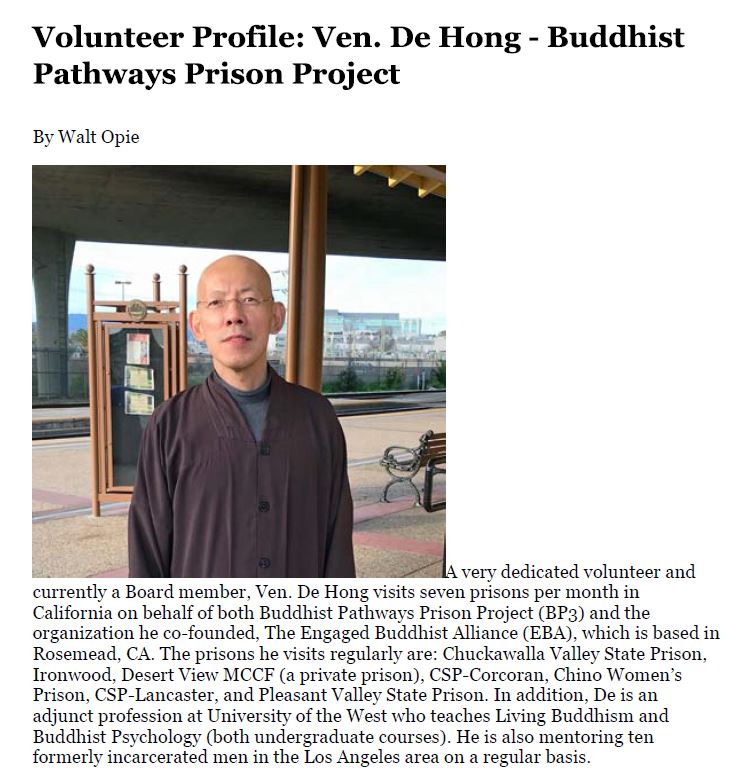

Although he was already a fully ordained Buddhist monk in the Chinese and Vietnamese Pure Land traditions (2006) with Thich Truyen Nhu as preceptor, De also ordained more recently in the Burmese Theravada tradition (2014) with Sayadaw U Khippa Panno as preceptor. He was inspired to ordain in the Theravada tradition after attending two retreats at the Insight Retreat Center (IRC) in Santa Cruz with Gil Fronsdal and Andrea Fella in 2013. He felt it would help him deepen his meditation practice further.

De first started going into prisons in September of 2013. “I went to Chuckawalla for the first time, accompanied by a sponsor,” De said. “When I first looked at all the razor wire on the double gates to get into the yard, it sent chills up my spine. I still try not to look at it—knowing it has electricity connected to it, thinking about how if someone touches it, they would be electrocuted.

“But inside, sitting in the circle next to the guys in the prison chapel, I had no fear at all, even though I had no clue what I was doing at first,” De said. “I thought the guys were normal. They talked and acted just like anyone that I have encountered outside. So I continued (to do prison work).

“As I learned more about them—we asked them to write down how they learned about Buddhism—it was very disturbing because some of them revealed what they had done (to be in prison),” De said. “It took me a while to learn to accept that or deal with it. They were very open, honest and truthful about who they were and their pasts. That’s the great thing about it. Most of them are still that way.”

I advise them to focus in the present moment and in their ability to transform.

De speculated that maybe those inside the prison confines share so openly with him because he is a monk. “I don’t ever ask them what they did. In (chaplaincy) training we were told not to ask them anything personal, but to let them reveal it. Yet somehow they tell me everything, especially if we are speaking on a one-on-one basis. I let go of my judgment. That is in the past, and I focus on who they are now. Otherwise, it would affect my ability to carry out my duties (as a volunteer chaplain). I advise them to focus in the present moment and in their ability to transform.”

Originally from Vietnam, De first came to the U.S. as a refugee. He and his younger brother escaped from the port of Saigon in the middle of the night on an overcrowded boat in September of 1981. The boat that carried them to safety was only about 30 feet long and 10 feet wide and had 142 people on board. A fishing vessel of some sort, De recalled, it was originally built to carry no more than ten people at a time.

“It was very traumatizing escaping Vietnam,” De said. “My brother was only 13, and I was 18. We spent six days and five nights on that boat with no food. For the first four days, there was (drinking) water, but we were only provided one teaspoon of water three times per day. And for the last two days, there was no water; it had run out.”

His family paid several ounces of gold per person for the two to make their harrowing voyage from Saigon to Malaysia—their initial destination. “We had to wait ten months on an island in Malaysia that held a refugee camp sponsored by the U.N. before the U.S. accepted us as refugees. (At the camp) I had a neighbor who worked for a social services organization. He filed the paperwork to sponsor me and my brother, and that’s how we ended up in Cleveland, Ohio.”

De and his brother landed in Cleveland during the winter months, having never lived in a cold climate before. “We had only two pairs of (warm weather) clothing, and even our sponsor didn’t buy us a jacket,” De said. He added that he had only $10 in his pocket at the time, so they couldn’t afford new clothes themselves, either.

They spoke no English when they first arrived, so there were many challenges to overcome, but in time both have carved out fulfilling lives here. His brother now lives in Los Angeles where both he and his wife work for the U.S. Postal Service. Their parents stayed back in Vietnam at first. They couldn’t all leave together, De said. Otherwise they would have lost their house and everything else back in Vietnam if it didn’t work out. In 1991, De sponsored his parents to come over to the U.S. He had become a U.S. citizen in 1988.

De first became interested in prison dharma work in the spring of 2013 when he heard about it from Dr. Lewis Lancaster, his professor at the University of the West, where De was working on his dissertation for a Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies. Dr. Lancaster said he wanted to start teaching Buddhism inside the prisons, which had been his intention for almost ten years. He held two meetings at the school for people who might be interested in joining him. “Out of the 20 people that came to the two meetings, only three people signed up, and I was one of them,” De said.

“My plan at the time was to give back to society, to America,” De explained. “I had a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering for free through a scholarship. My company paid for me to get a Master’s in Electrical Engineering, as well.” Yet at some point De realized he had something in common with many of the people he was meeting in prison. “I was physically and mentally abused by my alcoholic father growing up. Now, that’s one of the main reasons I want to help these (incarcerated) people. That is my realization after I visited the programs (for a while). In the beginning it was just to pay back society.

I realize most of them have been traumatized or abused, and they don’t know how to deal with it.

“The more I learn about the problems of why people commit crimes, I realize most of them have been traumatized or abused, and they don’t know how to deal with it. So when I work with them, I try to help them understand their past and how to heal their wounds. To me that’s what they need most. Even yesterday at Chuckawalla, I spoke with a lifer who does not know how to recognize what caused him to do what he did (his crime) in order to prepare himself for his parole board hearing. This guy is in his fifties! I spent a few minutes sharing on what he could do. I usually give them Buddhist psychology so they can understand why they did what they did and how to heal.”

When asked what has surprised him the most about going into prison, De said, “The injustice of our criminal justice system. Most of the offenders have been traumatized. And most of them have no money, so they end up having public defenders who often advise them to plead guilty and accept the sentence. There are not enough rehabilitative programs inside prisons. Many people’s lives and families are being ruined. And lastly, the change in people after they learn about Buddhism and meditation, if they maintain their meditation practice, is amazing.”

De said two women at Chino who learned meditation from him were eventually able to recognize the negative emotions as they arose without becoming identified with the emotion, and this allowed them to stop taking medications. Now they’re no longer labeled as having a mental illness. For the men he meets, De said they are able to be at peace with their environment and with who they are. “A lot of them have also helped their families by teaching them about meditation. Family members are able to connect with each other better after this.”

Lastly, De mentioned that through the University of the West, EBA now offers a certificate program in Buddhist Studies. Each course takes four months or more to complete. When the incarcerated student completes a course, they earn 1.2 continuing education units (CEUs) and a Chrono. “It will go into their C file,” De said. “The only problem is that they are not considered for milestone credits, so they receive no time off of their sentence. For that, we still need to get our program approved through CDCR in Sacramento.”